- Health Is Wealth

- Posts

- Tao Te Ching – Wikipedia

Tao Te Ching – Wikipedia

The Tao Te Ching ([tâu tɤ̌ tɕíŋ] (listen), (simplified Chinese: 道德经; traditional Chinese: 道德經; pinyin: Dàodé Jīng),[a] also known as Lao Tzu or Laozi,[5] is a Chinese classic text traditionally credited to the 6th-century BC sage Laozi. The text’s authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated.[6] The oldest excavated portion dates back to the late 4th century BC,[7] but modern scholarship dates other parts of the text as having been written—or at least compiled—later than the earliest portions of the Zhuangzi.[8]

The Tao Te Ching, along with the Zhuangzi, is a fundamental text for both philosophical and religious Taoism. It also strongly influenced other schools of Chinese philosophy and religion, including Legalism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, which was largely interpreted through the use of Taoist words and concepts when it was originally introduced to China. Many artists, including poets, painters, calligraphers, and gardeners, have used the Tao Te Ching as a source of inspiration. Its influence has spread widely outside East Asia and it is among the most translated works in world literature.[7]

The Chinese characters in the title (Chinese: 道德經; pinyin: Dàodéjīng; Wade–Giles: Tao⁴ Tê² Ching¹) are:

The first character can be considered to modify the second or can be understood as standing alongside it in modifying the third. Thus, the Tao Te Ching can be translated as The Classic of the Way’s Virtue(s),[citation needed] The Book of the Tao and Its Virtue, or The Book of the Way and of Virtue. It has also been translated as The Tao and its Characteristics,[3] The Canon of Reason and Virtue,[4] The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, and A Treatise on the Principle and Its Action.

Ancient Chinese books were commonly referenced by the name of their real or supposed author, in this case the “Old Master”, Laozi. As such, the Tao Te Ching is also sometimes referred to as the Laozi, especially in Chinese sources.[7]

The title “Daodejing”, with its status as a classic, was only first applied from the reign of Emperor Jing of Han (157–141 BCE) onward.[16] Other titles of the work include the honorific “Sutra (or “Perfect Scripture”) of the Way and Its Power” (Daode Zhenjing) and the descriptive “5,000-Character Classic” (Wuqian Wen).

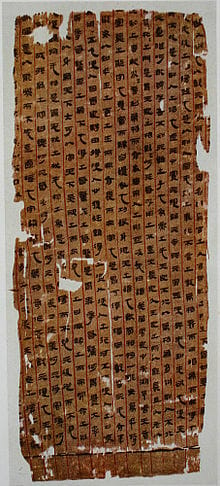

The Tao Te Ching has a long and complex textual history. Known versions and commentaries date back two millennia, including ancient bamboo, silk, and paper manuscripts discovered in the twentieth century.

Internal structure[edit]

The Tao Te Ching is a short text of around 5,000 Chinese characters in 81 brief chapters or sections (章). There is some evidence that the chapter divisions were later additions—for commentary, or as aids to rote memorization—and that the original text was more fluidly organized. It has two parts, the Tao Ching (道經; chapters 1–37) and the Te Ching (德經; chapters 38–81), which may have been edited together into the received text, possibly reversed from an original Te Tao Ching. The written style is laconic, has few grammatical particles, and encourages varied, contradictory interpretations. The ideas are singular; the style poetic. The rhetorical style combines two major strategies: short, declarative statements and intentional contradictions. The first of these strategies creates memorable phrases, while the second forces the reader to reconcile supposed contradictions.[17]

The Chinese characters in the original versions were probably written in zhuànshū (篆書 seal script), while later versions were written in lìshū (隸書 clerical script) and kǎishū (楷書 regular script) styles.

Historical authenticity of the author[edit]

The Tao Te Ching is ascribed to Laozi, whose historical existence has been a matter of scholarly debate. His name, which means “Old Master”, has only fueled controversy on this issue.[18]

The first reliable reference to Laozi is his “biography” in Shiji (63, tr. Chan 1963:35–37), by Chinese historian Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC), which combines three stories. In the first, Laozi was a contemporary of Confucius (551–479 BC). His surname was Li (李 “plum”), and his personal name was Er (耳 “ear”) or Dan (聃 “long ear”). He was an official in the imperial archives, and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the West; at the request of the keeper of the Han-ku Pass, Yinxi, Laozi composed the Tao Te Ching. Second, Laozi was Lao Laizi (老來子 “Old Come Master”), also a contemporary of Confucius, who wrote a book in 15 parts. Third, Laozi was the grand historian and astrologer Lao Dan (老聃 “Old Long-ears”), who lived during the reign (384–362 BC) of Duke Xian (獻公) of Qin.

Generations of scholars have debated the historicity of Laozi and the dating of the Tao Te Ching. Linguistic studies of the text’s vocabulary and rhyme scheme point to a date of composition after the Shijing yet before the Zhuangzi. Legends claim variously that Laozi was “born old”; that he lived for 996 years, with twelve previous incarnations starting around the time of the Three Sovereigns before the thirteenth as Laozi. Some Western scholars have expressed doubts over Laozi’s historical existence, claiming that the Tao Te Ching is actually a collection of the work of various authors.

Many Taoists venerate Laozi as Daotsu, the founder of the school of Dao, the Daode Tianjun in the Three Pure Ones, and one of the eight elders transformed from Taiji in the Chinese creation myth.

The predominant view among scholars today is that the text is a compilation or anthology representing multiple authors. The current text might have been compiled c 250 BCE, drawn from a wide range of texts dating back a century or two.[19]

Principal versions[edit]

Among the many transmitted editions of the Tao Te Ching text, the three primary ones are named after early commentaries. The “Yan Zun Version”, which is only extant for the Te Ching, derives from a commentary attributed to Han dynasty scholar Yan Zun (巖尊, fl. 80 BC – 10 AD). The “Heshang Gong Version” is named after the legendary Heshang Gong (河上公 “Riverside Sage”) who supposedly lived during the reign (180–157 BC) of Emperor Wen of Han. This commentary has a preface written by Ge Xuan (葛玄, 164–244 AD), granduncle of Ge Hong, and scholarship dates this version to around the 3rd century AD. The “Wang Bi Version” has more verifiable origins than either of the above. Wang Bi (王弼, 226–249 AD) was a famous Three Kingdoms period philosopher and commentator on the Tao Te Ching and the I Ching.

Tao Te Ching scholarship has advanced from archeological discoveries of manuscripts, some of which are older than any of the received texts. Beginning in the 1920s and 1930s, Marc Aurel Stein and others found thousands of scrolls in the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. They included more than 50 partial and complete “Tao Te Ching” manuscripts. One written by the scribe So/Su Dan (素統) is dated 270 AD and corresponds closely with the Heshang Gong version. Another partial manuscript has the Xiang’er (想爾) commentary, which had previously been lost.[20]

Mawangdui and Guodian texts[edit]

In 1973, archeologists discovered copies of early Chinese books, known as the Mawangdui Silk Texts, in a tomb dating from 168 BC.[7] They included two nearly complete copies of the text, referred to as Text A (甲) and Text B (乙), both of which reverse the traditional ordering and put the Te Ching section before the Tao Ching, which is why the Henricks translation of them is named “Te-Tao Ching”. Based on calligraphic styles and imperial naming taboo avoidances, scholars believe that Text A can be dated to about the first decade and Text B to about the third decade of the 2nd century BC.[21]

In 1993, the oldest known version of the text, written on bamboo tablets, was found in a tomb near the town of Guodian (郭店) in Jingmen, Hubei, and dated prior to 300 BC.[7] The Guodian Chu Slips comprise about 800 slips of bamboo with a total of over 13,000 characters, about 2,000 of which correspond with the Tao Te Ching.

Both the Mawangdui and Guodian versions are generally consistent with the received texts, excepting differences in chapter sequence and graphic variants. Several recent Tao Te Ching translations utilize these two versions, sometimes with the verses reordered to synthesize the new finds.[22]

Themes[edit]

The text concerns itself with the Dao (or “Way”), and how it is expressed by virtue (com). Specifically, the text emphasizes the virtues of naturalness (ziran) and non-action (wuwei).[19]

Translations[edit]

The Tao Te Ching has been translated into Western languages over 250 times, mostly to English, German, and French. According to Holmes Welch, “It is a famous puzzle which everyone would like to feel he had solved.”[24] The first English translation of the Tao Te Ching was produced in 1868 by the Scottish Protestant missionary John Chalmers, entitled The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality of the “Old Philosopher” Lau-tsze. It was heavily indebted to Julien’s French translation and dedicated to James Legge,[2] who later produced his own translation for Oxford’s Sacred Books of the East.[3]

Other notable English translations of the Tao Te Ching are those produced by Chinese scholars and teachers: a 1948 translation by linguist Lin Yutang, a 1961 translation by author John Ching Hsiung Wu, a 1963 translation by sinologist Din Cheuk Lau, another 1963 translation by professor Wing-tsit Chan, and a 1972 translation by Taoist teacher Gia-Fu Feng together with his wife Jane English.

Many translations are written by people with a foundation in Chinese language and philosophy who are trying to render the original meaning of the text as faithfully as possible into English. Some of the more popular translations are written from a less scholarly perspective, giving an individual author’s interpretation. Critics of these versions claim that their translators deviate from the text and are incompatible with the history of Chinese thought.[27] Russell Kirkland goes further to argue that these versions are based on Western Orientalist fantasies and represent the colonial appropriation of Chinese culture.[28][29] Other Taoism scholars, such as Michael LaFargue[30] and Jonathan Herman,[31] argue that while they don’t pretend to scholarship, they meet a real spiritual need in the West. These Westernized versions aim to make the wisdom of the Tao Te Ching more accessible to modern English-speaking readers by, typically, employing more familiar cultural and temporal references.

Translational difficulties[edit]

The Tao Te Ching is written in Classical Chinese, which poses a number of challenges to complete comprehension. As Holmes Welch notes, the written language “has no active or passive, no singular or plural, no case, no person, no tense, no mood.”[32] Moreover, the received text lacks many grammatical particles which are preserved in the older Mawangdui and Beida texts, which permit the text to be more precise.[33] Lastly, many passages of the Tao Te Ching are deliberately vague and ambiguous.

Since there are no punctuation marks in Classical Chinese, it can be difficult to conclusively determine where one sentence ends and the next begins. Moving a full-stop a few words forward or back or inserting a comma can profoundly alter the meaning of many passages, and such divisions and meanings must be determined by the translator. Some editors and translators argue that the received text is so corrupted (from originally being written on one-line bamboo strips linked with silk threads) that it is impossible to understand some chapters without moving sequences of characters from one place to another.

See also[edit]

^Less common former romanizations include Tao-te-king, Tau Tĕh King[2] and Tao Teh King.[3][4]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

^ a bChalmers (1868), p. v.

^ a b cLegge & al. (1891).

^ a bSuzuki & al. (1913).

^Ellwood, Robert S. (2008). The Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-4381-1038-7.

^Eliade (1984), p. 26

^ a b c d eChan (2013).

^Creel 1970, What is Taoism? 75

^Seidel, Anna. 1969. La divinisation com Lao tseu dans le taoïsme des Han. Paris: École française d’Extrême‑Orient. 24, 50

^Austin, Michael (2010). “Reading the World: Ideas that Matter”, p. 158. W. W. Norton & Company, New York. ISBN 978-0-393-93349-9.

^Feng Cao. “Daoism in Early China: Huang-Lao Thought in Light of Excavated Texts”; Palgrave Macmillan, 2017

^ a bChan, Alan, “Laozi“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), retrieved 3 February 2020

^William G. Boltz, “The Religious and Philosophical Significance of the ‘Hsiang erh’ “Lao tzu” 相 爾 老 子 in the Light of the “Ma-wang-tui” Silk Manuscripts”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 45 (1982), pp. 95ff

^Boltz (1993), p. 284

^See Lau (1989), Henricks (1989), Mair (1990), Henricks 2000, Allan and Williams 2000, and Roberts 2004

^Welch (1965), p. 7

^“The Taoism of the Western Imagination and the Taoism of China: com-Colonizing the Exotic Teachings of the East” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2007.

^Taoism: the enduring tradition – Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

^[1][dead link]

^Review of Tao Te Ching: A Book about the Way and the Power of the Way by Ursula K. Le Guin, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 66 (1998), pp. 686–689

^Welch (1965), p. 9

^Henricks (1989), p. xvi

Sources[edit]

Julien, Stanislas, ed. (1842), Le Livre com la Voie et com la Vertu, Paris: Imprimerie Royale. (in French)

Chalmers, John, ed. (1868), The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality of the “Old Philosopher” Lau-tsze, London: Trübner & Co.

Legge, James; et al., eds. (1891), The Tao Teh King, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XXXIX, Sacred Books of China, Vol. V, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Giles, E; et al., eds. (1905), The Sayings of Lao Tzu, The Wisdom of the East, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.

Suzuki, Daisetsu Teitaro; et al., eds. (1913), The Canon of Reason and Virtue: Lao-tze’s Tao Teh King, La Salle: Open Court.

Wieger, Léon, ed. (1913), Les Pères du Système Taoiste, Taoïsme, Vol. II, Hien Hien(in French).

Mitchell, Stephen (1988), Tao Te Ching: A New English Version, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 9780061807398.

Henricks, Robert G. (1989), Lao-tzu: Te-tao ching. A New Translation Based on the Recently Discovered Ma-wang-tui Texts, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 0-345-34790-0

Lau, D. C. (1989), Tao Te Ching, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, ISBN 9789622014671

Mair, Victor H., ed. (1990), Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, New York: Bantam Books.

Bryce, Derek; et al., eds. (1991), Tao-Te-Ching, York Beach: Samuel Weiser.

Addiss, Stephen and Lombardo, Stanley (1991) Tao Te Ching, Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

Ariel, Yoav, and Gil Raz. “Anaphors or Cataphors? A Discussion of the Two qi 其 Graphs in the First Chapter of the Daodejing.” PEW 60.3 (2010): 391–421

Boltz, William (1993), “Lao tzu Tao-te-ching“, Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 269–92, ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

Chan, Alan (2013), “Laozi”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford: Stanford University.

Cole, Alan, “Simplicity for the Sophisticated: ReReading the Daode Jing for the Polemics of Ease and Innocence,” in History of Religions, August 2006, pp. 1–49

Damascene, Hieromonk, Lou Shibai, and You-Shan Tang. Christ the Eternal Tao. Platina, CA: Saint Herman Press, 1999.

Eliade, Mircea (1984), A History of Religious Ideas, 2, translated by Trask, Willard R., Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Kaltenmark, Max. Lao Tzu and Taoism. Translated by Roger Greaves. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1969.

Klaus, Hilmar Das Tao der Weisheit. Laozi-Daodejing. English + German introduction, 140 p. bibliogr., 3 German transl. Aachen: Mainz 2008, 548 p.

Klaus, Hilmar The Tao of Wisdom. Laozi-Daodejing. Chinese-English-German. 2 verbatim + 2 analogous transl., 140 p. bibl., Aachen: Mainz 2009 600p.

Kohn, Livia; et al. (1998), “Editors’ Introduction”, Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 1–22.

Komjathy, Louis. Handbooks for Daoist Practice. 10 vols. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute, 2008.

LaFargue, Michael; et al. (1998), “On Translating the Tao-te-ching“, Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 277–302.

Welch, Holmes (1965) [1957], Taoism: The Parting of the Way, Boston: Beacon Press

External links[edit]

Other online English translations[edit]

Legge, Suzuki, and Goddard’s translations side-by-side, along with the original text[permanent dead link]

The recent translations of Red Pine, Thomas Cleary, and Moss Roberts side-by-side

The Tao Te Ching, Frederic H. Balfour

The Tao Teh King, Aleister Crowley

Daode Jing, Charles Muller

The Living Dao: The Art and Way of Living A Rich & Truthful Life, Lok Sang Ho, Lingnan University

老子 Lǎozǐ 道德經 Dàodéjīng Wáng Bì 王弼, Pīnyīn 拼音, analysis, verbatim, analogous, poetic, comments, notes, Hilmar Alquiros

Dima Monsky, Sarita La Cubanita (13 November 2018). Dao com Ching ANT (Adaptation is Not Translation). Retrieved 16 January 2019.