- Health Is Wealth

- Posts

- The classical Chinese – Chinese food and natural health Chinese culture

The classical Chinese – Chinese food and natural health Chinese culture

The classical Chinese

The classical Chinese (Chinese: 古文; pinyin: gǔwén) is a traditional form of written Chinese based on the grammar and vocabulary of ancient states of the Chinese language, which makes it a different written language of any written Chinese language contemporary.

The term sometimes refers to the literary Chinese (文言文, wényánwén), generally considered the language which replaced the Chinese. However, the distinction between on one hand the classical Chinese and Chinese literature is blurred.

The classic Chinese literary or writing to the attention of the Koreans is known to hanmun; for the Japanese, it is the Kanbun; Vietnam is the Hán Văn (all three 漢文 written, “writes Hans language”).

The distinction between on one hand the Chinese and modern Chinese is blurred. Classical Chinese writing was used until the early twentieth century in all formal written in China but also in Japan, Korea and Vietnam. Among the Chinese, classical Chinese writing has now been largely replaced by written Chinese Contemporary (白話, baihua), a substantially closer style of spoken Mandarin Chinese, while also non-Chinese speakers speakers are now virtually abandoned Classical Chinese in favor of local vernaculars.

definitions

Although the Chinese literary classic Chinese expressions are generally considered as equivalent, however it should be somewhat nuanced. Sinologists tend to see them as two different things, classical Chinese is considered an older state of the written language.

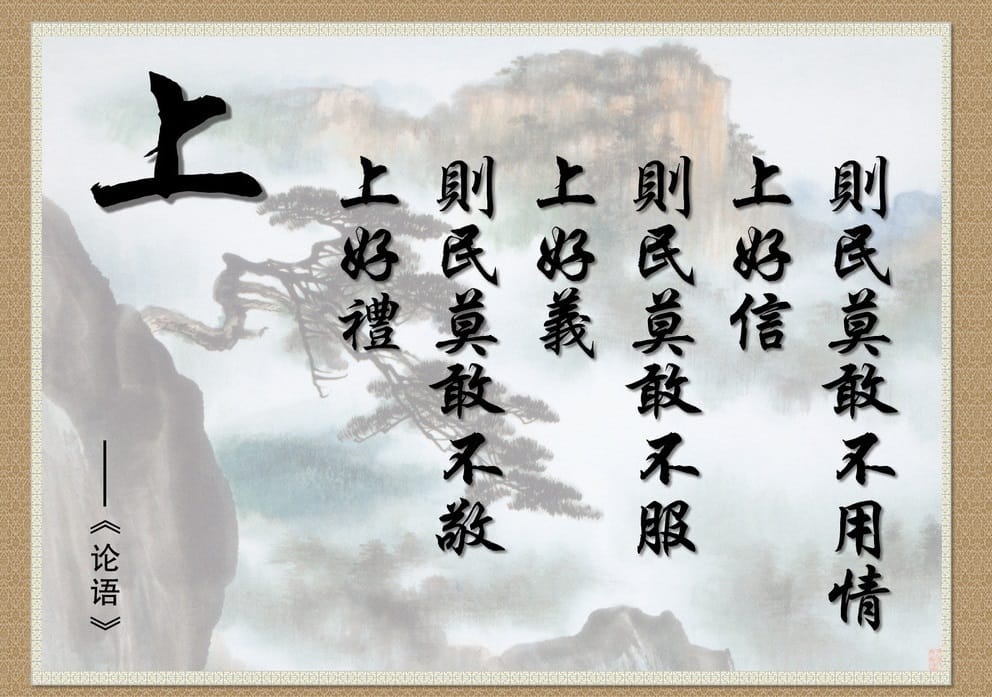

According to various academic definitions, classical Chinese (古文, gǔwén “ancient writing,” or more literally 古典 漢語 gǔdiǎn hànyǔ “classic writing Hans”) refers to the Chinese written language of the first millennium BC: the Zhou Dynasty, and in particular to the period of the Spring and Autumn to the end of the Han dynasty. Classical Chinese is therefore the language used in many of the Chinese standard reference books, such as the Analects of Confucius, the Mencius and the Dao com Jing (the language of older texts, such as Classical poetry, is sometimes called Archaic Chinese ).

Literary Chinese (文言文, wényánwén “literary writing,” or more commonly simply 文言 Wenyan) is the form of written Chinese used between the end of the Han Dynasty to the early twentieth century, when it was replaced by the writings written Chinese vernacular (baihua). Literary Chinese diverged more Chinese dialects the Chinese classic, having evolved through the ages so increasingly divergent spoken Chinese. However, the literary Chinese is mainly based on the Chinese classic, and people writing in literary Chinese did not hesitate to take the classic Chinese elements in their literary Chinese. These two written forms have always been relatively close, although the Chinese literary diverged from its source over the centuries.

This situation, the Chinese literary use as a common language between China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam, can be compared to that of the universal use of the Latin language which survived (including academia) despite local appearance of the Romance languages, or to the current situation of classical Arabic and its local varieties. Romance languages have continued to evolve, influencing Latin texts that were their contemporaries, so that by the Middle Ages, the Latin language included various new adaptations that would have posed a problem to the Romans. It became even Greek. The coexistence of the Chinese classic with local languages in Korea, Japan, Vietnam can be compared to the use of Latin in countries that do not use Latin-based language such Germanic, Slavic languages where instead of Arabic in India or Persia.

Pronunciation

The shape character for small seal “harvest” (which later will mean “year”) probably comes from the character “person.” A hypothetical pronunciation of these characters explain this similarity.

The Chinese are not alphabetical writing, and evolution does not reflect the evolution of pronunciation. Archaic Chinese oral reconstruction efforts remain extremely difficult. Classical Chinese is therefore not read by trying to do with pronunciation prevailing at the time, which remains hypothetical. Readers generally use the pronunciation which is the language in which they are usually expressed (Mandarin, Cantonese …) or, for some languages such Minnan Chinese, with a series of standard pronunciations planned for the Chinese classic, legacy of ancient customs. In practice, all Chinese languages combine these two techniques, Mandarin and Cantonese, for example, using some characters of old typed or pronunciations, but generally for other contemporary pronunciation.

Korean players, Japanese, Vietnamese or Chinese classical use clean pronunciations in their language. For example, the Japanese pronounce the on’yomi or (more rarely) kun’yomi, which are used for the pronunciation kanji (Chinese characters used in Japanese). Kanbun a specific system to express the Chinese classic, is also used.

Since the archaic pronunciation of Chinese or other historical forms of Chinese oral (as the Middle Chinese) have been lost, texts and characters that made them have since lost their rhymes and poetry (most frequently in Mandarin Cantonese). Poetry and writing based on the rhymes were therefore less coherence and musicality at the time of their composition. However, some features of modern dialects seem closer to the archaic or medieval Chinese, by preserving the rhyme scheme. Some think wenyan literature, especially poetry, is best preserved when read in some dialects, which are closest to the pronunciation of Archaic Chinese. It is basically exits languages of southern China, such as Cantonese or Minnan.

Another important phenomenon that appears when reading the classical Chinese is homophony, or words to meaning and possibly in different handwriting, that are pronounced the same way. Up to more than 2500 years of pronunciation change separates Classical Chinese nowadays spoken Chinese languages. Therefore, many characters that originally had a different pronunciation have since become homophones in Chinese language or Vietnamese, Korean or Japanese. There is a famous classical Chinese essay written in the early twentieth century by the linguist R. Y. Chao called The Poet eater lion in his lair stone that illustrates this phenomenon. The text is perfectly understandable when read, but it contains only characters now all pronounced shi (with four tones: shi¹, shi², shi³ and shi⁴), which makes it incomprehensible to hearing . Literary Chinese written language by its nature using a logographic writing, adapts more easily to homophones, which poses no problem with the traditional vector writing, but that was to be a source of ambiguity oral, including the speakers of the archaic oral language.

The situation is similar to that of certain words in other languages that are homophones, such as eg in French “saint” (Latin: Sanctus) and “breast” (Latin: sinus). These two words have the same pronunciation, but different origins, which is made by how they are written; however they originally had different pronunciations, which is written track. The French spelling is not that old of a few hundred years and makes for share account old pronunciations. Chinese writing is by contrast several millennia old, and logographic, and homographs are therefore significantly more present than in the writings of languages based on pronunciation.

Grammar and vocabulary

The guwen more than wenyan baihua differs from its style that appears as extremely compact for modern Chinese speakers, and using a different vocabulary. In terms of conciseness and compactness, for example, the guwen rarely uses words of two characters, they are substantially all of a single syllable. This contrasts sharply with the modern Chinese words where two characters are a good part of the lexicon. Literary Chinese also generally more pronouns that modern language. The particularly Mandarin uses only one pronoun for the first person ( “I”, “me”), while the Chinese literary several, including several for honorary purposes, and others for specific uses (first collective person, first person possessive, etc.).

This phenomenon is partly because of polysyllabic words evolve Chinese homophones to raise ambiguities. This is similar to the phenomenon in English pen / pin merger (in) Southeast United States. Because of the sounds are similar, there may be a confusion, resulting in the regular addition of a term to disambiguate, eg “writing pen” and “stick pin”. Likewise, modern Chinese has emerged many polysyllabic words to disambiguate homophones monosyllabic words, which appear today as homophones, but who were not in the past. Since the guwen ostensibly wants an imitation of archaic Chinese, it tends to eliminate any word plurisyllabique present in modern Chinese. For the same reason, the guwen has a strong tendency to drop subjects, verbs, objects, etc., when they are included in one way or another, or can be inferred, tending to simplicity and optimization of form; guwen the example has developed a neutral pronoun ( “it” in English as a subject) very late. A sentence containing 20 characters baihua not often that includes 4 or 5 in guwen.

There are also differences in the vector, in particular for grammatical particles, as well as to the syntax.

In addition to grammatical differences and vocabulary, guwen is distinguished by literary and cultural differences: there is a desire to maintain parallelism and rhythm, even in prose, and extensive use of cultural allusions.

Grammar and lexicon of classical Chinese are somewhat different between classical Chinese and Chinese literature. For example, the rise of 是 (shì modern Mandarin) as a copula ( “be”) rather than a demonstration of proximity ( “it”) is typical of literary Chinese. It also tended to use more combinations of two characters that classic.

Learning and use [edit | modify the code]

The wenyan was the only form used for Chinese literature to the May 4th Movement and was also much used in Japan and Korea. Ironically, the classical Chinese was used to write the Hunmin Jeongeum, work to promote the modern Korean alphabet (Hangeul), as well as a Review of Hu Shi in which he opposed the classical Chinese and for the baihua. Among the exceptions to texts written in wenyan included some new Chinese vulgar including Dream of the Red Chamber, considered popular at the time.

Today, the real wenyan is sometimes used for ceremonial or formal circumstances. The National Anthem Republic of China (Taiwan) for example, is written in wenyan. In practice, there is a continuum between the accepted baihua and wenyan. For example, numerous references and salutations include typical expressions wenyan, a little example of some contemporary use of Latin in the French language (such es, ad interim, mutatis mutandis, deus ex maxchina). The personal and informal letters include more baihua, if not in some cases some wenyan expressions, depending on the subject or the recipient’s level of education and the person writing, etc. A fully letter written in wenyan might seem old China, even pretentious, but might impress some.

Most people who have received education at the secondary level are in principle capable of reading somewhat wenyan because this ability (to read but not write) the responsibility of the Chinese lower and upper secondary education, and matters subject to controls and tests. The wenyan is usually presented by a classic text in this language, accompanied by an explanatory glossary baihua. The tests usually consist of a version of a text wenyan to baihua, sometimes with multiple choices.

In addition, many literary works in wenyan (such as those of Tang poetry) are of major cultural significance. Despite this, even with a good knowledge of vocabulary and grammar, the wenyan can be difficult to understand, even by people of native Chinese and mastering the contemporary Chinese writing, because of the many literary references, allusions and the concise style.

Click here to read more about Chinese culture